OSKA: growing need for foreign labour

Looking ahead over the next decade, the Estonian labour market will be short of around 1,400 top specialists and 700 skilled workers every year, and the need for them cannot be met by Estonian graduates. The involvement of some foreign labour is inevitable, according to a recent OSKA study.

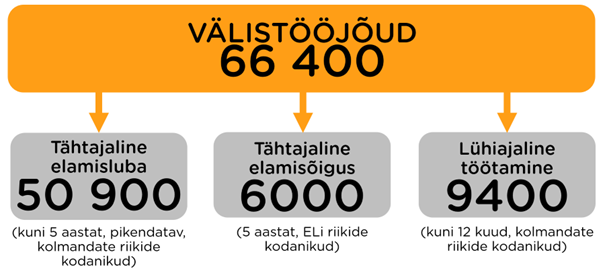

2023. In 2007, Estonia employed 66 400 foreign workers, which accounted for 9% of the total annual employment. The number of foreign workers in the Estonian labour market has almost doubled in 2019-2023. Without the Ukrainian refugees, the increase would probably have been smaller, although by 2021 the share of foreign labour had already risen to 7%.

Estonia’s labour migration policy is based on an immigration quota (0.1% of the population) and its specificities, but the quota restricts only labour migration of third-country nationals with a temporary residence permit, which in 2023 accounted for only 12% of workers with a temporary residence permit in Estonia.

“In addition to labour migration and the number of beneficiaries of international protection, Estonia’s labour market is also affected by migration within the European Union, family migration, learning migration,” said Silja Lassur, OSKA’s research manager.

“People who come to Estonia for different purposes fill different gaps in the labour market,” said Lassur. He pointed out that short-term residents tend to work in skilled and unskilled occupations. International protection beneficiaries also find it easiest to enter the labour market through unskilled and skilled jobs, where local language skills are not required. One third of those who come to work are professionals. EU nationals are also more likely to come for a professional position.

Labour shortages remain

OSKA analyst Andres Viia said that the need for foreign labour is likely to grow in the coming decade: “The sustainable development of Estonia’s economy and society depends on the availability and quality of labour as an important aspect. At the same time, Estonia’s population is ageing and the number of young people entering the labour market is not sufficient to cover the number of those leaving it.”

Viia acknowledged that the state can alleviate labour shortages through various measures, including education policy, reducing unemployment, upgrading the skills and qualifications of the local workforce, etc., but internal resources are still limited and the involvement of foreign labour is essential to some extent.

OSKA estimates that there will be a shortage of around 1,400 top specialists on the Estonian labour market every year until 2035. The biggest labour shortages will be in ICT, education, healthcare and manufacturing. In ICT and manufacturing, the shortages can be reduced by hiring foreign workers.

In terms of skills, there is a shortfall of 700 skilled workers per year. Unless other solutions are found to meet labour needs, foreign labour will be needed in the transport and storage, social work and manufacturing sectors.

The share of foreign workers in the unskilled labour force is currently high due to the presence of the Ukrainian refugee labour force, which is expected to decline in the next 10 years. At the same time, however, the number of unskilled workers is expected to decrease over the years, which means that there is unlikely to be a need to bring in unskilled workers at current levels.

According to Ulla Saare, Deputy Secretary of State for Labour and Equal Opportunities Policy at the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Communications, the OSKA report is essential for a data-driven debate on skilled labour in Estonia.

“Labour shortages have long been a major concern for Estonian companies, and Estonia’s assessment of the availability of skilled labour is one of the lowest in the EU. The state can address the problem in a number of ways, including increasing the birth rate, up-skilling and retraining of the existing workforce and increasing labour productivity. However, these are not quick fixes, and in many sectors labour shortages are already critical. Foreign labour could fill these gaps and complement the skills of the local workforce,” Saar explained.

Migration policy must set clear objectives

The OSKA study notes that Estonia’s migration policy is fragmented, complex and diverse, making it difficult for employers and migrants alike to navigate all the conditions.

To better target and use foreign labour in the Estonian labour market in the future, labour migration policy as a whole needs to be reviewed. It is necessary to establish common objectives and general principles for labour migration policy, including links with other types of migration. Labour migration policy could set out both short- and long-term objectives and principles, which would minimise disparities but leave the system flexible enough to allow for corrections where necessary.

Check out the OSKA survey: “Foreign labour needs by 2035”.

Take part in the information session

Take part in an information session organised by the Chamber of Vocational Education and Training (SA Kutsekoja), where the new OSKA study “External labour needs until 2035” will be presented.

The information session will take place on Thursday 27 March 2025 at 11.00 on the Zoom environment – https://us02web.zoom.us/…/register/7FzmKxDdTjG3zk-KRvmISA

The results of the survey will be presented by Silja Lassur, OSKA Survey Manager, and Andres Viia, OSKA Analyst.